Grand Designs: Living in the Wild

Remote landscapes presented challenges for these self-builders

Grand Designs: Living in the Wild, originally broadcast in 2015, saw Kevin McCloud explore some of the best Grand Designs projects built in remote places. Not only are the homes innovative and ground breaking, but the self-builders are pioneers in ‘wilderness architecture’.

Not only does building a home in a harsh landscape present its challenges, living off-grid also requires a degree of resilience.

‘If you live in a remote area you will have to be self-sufficient,’ says architectural curator Sarah Gaventa. ‘You need to think about what happens if you get cut off, what happens if you can’t get supplies, if you need to make a living and how do you do that. If you are not prepared to be self-sufficient, even for small amounts of time, you would really struggle.’

But there are clear advantages: ‘It’s almost the ideal condition for an architect to be in an environment where there aren’t any planners breathing down your neck or hundreds of people putting in objections,’ adds Sarah. ‘And it’s the vision of someone who is obviously passionate about being there and has a very clear idea about how they want to live.’

There are three key questions to consider when deciding whether ‘living in the wild’ is for you:

- How will you produce or obtain food?

- How will you heat and power your home?

- How will you deal with waste products?

The next thing to consider is how to build your home. Access to remote plots can be tricky, weather conditions can be harsh, so traditional build methods may not be suitable.

But these Grand Designers embraced the challenge with aplomb. From a home built in the middle of a windy airfield, to a Passivhaus hidden under a centuries-old barn and a curvy, handcrafted home, these are the unforgettable projects featured on Grand Designs: Living in the Wild.

The airfield house

Extreme weather conditions can be a Grand Designer’s worst nightmare, but architect Richard Murphy came up with an elegant solution for a robust industrial style building that could withstand stormy conditions, but still look lightweight.

Unusually, the airfield house was built on Scotland’s Strathaven Airfield for flying fanatics Colin MacKinnon and Marta Briongo – with 100mph winds to contend with, an aerodynamic, curved corrugated roof was chosen as they feared slate tiles would be ripped off.

The first floor has the traditional 20th century Scottish layout of three sections. These include a bedroom and living room at opposite ends, with the kitchen in the middle. This floor is where the couple spend most of their time. Consequently, the living room is overlooked by a mezzanine office platform, which Marta uses as an art studio. There’s even a swing for Marta to practice her aerial gymnastics.

The couple have named the house Aluminia Meadownia because it’s clad in corrugated aluminium and the airfield looks like a wild flower meadow in summer.

The airfield house from Grand Designs: Living in the Wild. Photo: Douglas Gibb

Cotswolds Passivhaus

You might not expect to find England’s first-ever Passivhaus in the middle of the Cotswolds, let alone hidden under a centuries-old barn.

The planning rules dictated that the house had to be invisible, so owners and architects Helen and Chris Seymour-Smith created what Helen referred to as ‘loft-style living underground’.

Despite numerous predecessors failing to get permission, the pair succeeded due to the project’s pioneering eco credentials. It’s wrapped top-to-toe in foam insulation, triple glazed, and the walls and roof are made from pre-cast eco-friendly concrete panels that are designed to store heat.

Plus, the screed floor is composed of 100% recycled materials and the heat recovery system ensures the temperature stays at around 20°C, even in winter.

The Cotswolds Passivhaus. Photo: Chris Tubbs

Hexagonal Hobbit house

Despite having no experience, Kelly and Masako Neville decided to build a sustainable home on a 6.2-acre plot in the Cambridgeshire fens that would enable them to produce their own food and energy.

The unusual six-sided Hobbit house is constructed from oak, clay plaster, lime render and a cedar shingle roof and sits on stilts for flood protection, and to reduce the amount of concrete needed in the build.

Home-grown willows feed the outside furnace, while a ground-source heat pump delivers underfloor heating, and there’s a wind turbine for backup power.

‘The house appears to float across the fenland, a hexagonal, galleon-cum-miniature Globe Theatre,’ said Kevin McCloud. ‘It’s a striking example of hard-core sustainable construction and living.’

The Hexagonal Hobbit house from Grand Designs: Living in the Wild. Photo: Chris Tubbs

Northumberland mill conversion

The biggest challenge that Stefan and Ania Lepkowski set themselves with this expansive mill conversion project was not just that they built the bulk of their home with their own hands, but also the range of skills and materials this involved. The project included restoring a derelict cottage, building a new one from reclaimed stone, plus a modern glass and steel building to link them, and a basement.

The project included restoring a derelict cottage, building a new one from reclaimed stone, plus a modern glass and steel building to link them, and a basement.

When Stefan first saw the Georgian mill house 20 years ago it was love at first sight, though it didn’t come on the market left for another 15 years. As luck would have it, that was when he and Ania were house hunting and had the funds to buy it.

He’s reluctant to say how much the final bill was, but he does say it will be a few years before they’re comfortable with the amount. But then again, this house was never about money. It was about passion.

The Northumberland mill conversion. Photo: Jefferson Smith

Herefordshire dugout

The Grand Designs Dugout in Herefordshire was a truly unique project. It started in 2000, when Ed and Rowena Waghorn bought an eight-acre plot.

Ed, an estate manager, wanted to do most of the work himself, constructing a timber-framed house using recycled materials, timber from the nearby woods and stone from around the site.

A variety of insulation materials keeps the house warm and energy-efficient. Solar voltaic panels for electricity team with thermodynamic panels for hot water.

Moreover, passive solar gain and gathered firewood heat specific spaces. Local foraged timber including chestnut, ash and cedar has been used throughout, along with stone and lime. The earth floor in the hall is made with clay from the couple’s land and straw from local fields.

The Herefordshire dugout from Grand Designs: Living in the Wild. Photo: Andrew Wall

A wooden house in West Sussex

Woodsman Ben Law wanted to build his wooden forest home using the surrounding, natural resources, to help it blend into the landscape.

He acquired Prickly Nut Wood in 1992 through barter – his labour was exchanged for land – and from then until the house was erected 10 years later, he lived in a caravan.

By using traditional building techniques, packing his house with solar panels and wind turbines, and employing the help of many friends, Ben managed to keep costs low – the build cost just £28,000 and took eight months.

The walls are made from 300 barley bales, which were shaped with chainsaws, fixed into the wooden framework with chestnut stakes and plastered with lime.

Ben Law’s wooden home. Photo: Stephen Morley

The Brittany earthship home

Daren Howarth and Adi Nortje’s desire to build their home in an eco-friendly way freed them from the shackles of a mortgage and hefty running costs. Water is harvested from the rain, windows face the sun to capture heat and the walls are made from high thermal mass materials such as earth.

With insulation board made from recycled car windscreens, walls decorated with hundreds of glass bottles, a kitchen built partly with salvaged oak and a main structure made from around 200 tons of earth, excavated from the site and rammed into 1,000 car tyres – the Grand Designs earthship house in Brittany, France, brings a whole new meaning to the phrase ‘waste not, want not’.

It also harnesses modern technology to turbocharge it with more of nature’s power. As well as south-facing windows that capture the sun’s warmth, Daren and Adi installed a 2.3kW array of photovoltaic panels on the roof to transform the solar energy into electricity.

The Brittany earthship house from Grand Designs: Living in the Wild. Photo: Chris Tubbs

A Welsh forester’s lodge

Grand Designers Nigel Hussey and wife Tamayo transformed a Welsh forester’s lodge into a modern family dwelling influenced by Tamayo’s homeland, Japan. In May 2009 Nigel and Tamayo got in touch with some local architects to discuss plans to rebuild and remodel their house.

They wanted a timber-framed property made from Japanese larch and clad in the same material – partly for its appropriate name and partly because they had read up on the material’s strength and suitability for house construction.

Upstairs on the first-floor galleried landing you can take full advantage of the landscape and as you follow the second staircase to the wet room and roof terrace you’re met with breath taking views down the valley.

The Japanese house peeks out from the trees as you drive past and, with its Japanese larch cladding, the dwelling suits its wooded surroundings perfectly.

The Welsh forester’s lodge. Photo: Chris Tubbs

An eco-community project

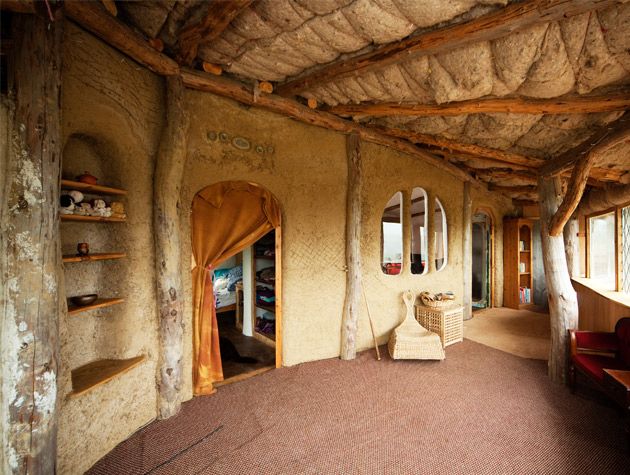

As part of an eco-village in west Wales, Simon and Jasmine Dale set out to hand-build an eco-home, starting with only £500 in the bank.

A seven-acre smallholding, the plot forms part of the Lammas eco-community, endorsed by the Welsh Assembly under its OnePlanet Development policy.

The south-facing hillside was excavated, before a retaining wall was constructed made from earth-filled bags. The main building structure and roof were made from larch, with lime-rendered straw bales filling the gaps and sheepswool for insulation.

A damp-proof membrane offers protection, while a grass roof blends the structure into the hillside.

A hand-built eco home in Wales from Grand Designs: Living in the Wild. Photo: Malgosia Czarniecka Lonsdale

‘I think one of the great appeals of living off-grid is that attractiveness of not being reliant on infrastructure that modern society provides us with – the support system of power, energy and goods that we rely on,’ says Kevin McCloud while filming Grand Designs: Living in the Wild.

‘Instead, you survive on what you’ve got,’ he continues. ‘It gives a sense of satisfaction, like being master of your own destiny.’