Hand-built eco home in Wales

Simon and Jasmine Dale set out to hand-build an eco home with only £500 in the bank

As part of an eco-village in west Wales, Simon and Jasmine Dale set out to hand-build an eco-home, starting with only £500 in the bank.

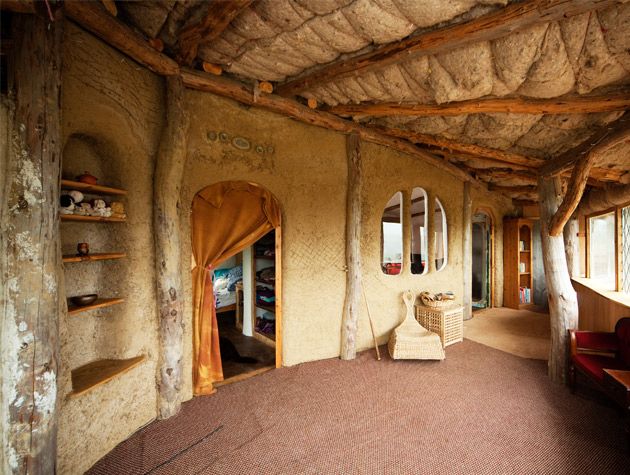

The story of Simon and Jasmine Dale’s Pembrokeshire home starts with the couple’s lifestyle and livelihood. Architects talk about taking a holistic approach, but that maxim rings pretty hollow in the face of a house that was built from trees felled on its own plot, that is completely off-grid, and that created virtually zero waste.

Photo: Malgosia Czarniecka Lonsdale

As Kevin McCloud put it when their project appeared on Grand Designs last year, ‘this is the lowest of low-impact houses.’ It might be the cheapest of low-impact houses, too: when Simon and Jasmine started the build, they had only £500 in the bank.

The couple had some experience of building with round-poled timber and straw bales before they found their present plot, but it was the permanence of this new venture that inspired them to be more ambitious in their plans. This is to be a home for life. ‘This time, we are making a home we know will last,’ says Simon.

‘Previous projects I have built for our family have been on other people’s land, so we knew we would only need them for a couple of years.’ This time, he wanted to up the spec, experimenting with the idea of a house that could have modern comforts, such as underfloor heating, a generous bathroom and a carefully crafted finish, without compromising his ecological principles.

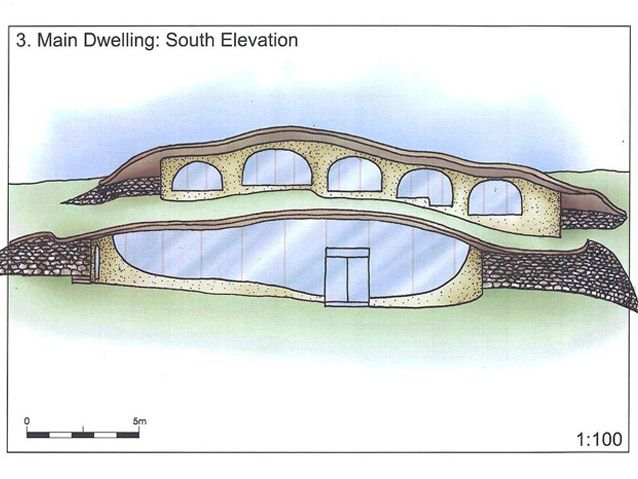

The TV programme was one of those episodes where you make note of the start date – 2012 – and know it’s going to be an interesting ride. A seven-acre smallholding, the plot forms part of the Lammas eco-community, endorsed by the Welsh Assembly under its One Planet Development policy.

In exchange for planning permission for the eco-home, the smallholders were given five years to demonstrate that 75% of their everyday basic needs could be met from the land. The need to set up the small business side of the smallholding, both to make money and meet the planning conditions, meant the house was sometimes sidelined for months at a time.

Photo: Malgosia Czarniecka Lonsdale

On the planning side, the house’s sustainability was given more weight than would be usual, which meant there were more lenient allowances for building methods. This was just as well, because it would have been impossible to build exactly to plan – the construction method uses timber poles, which do not conform to the strict dimensions of the average building material.

To start with, part of the south-facing hillside was excavated, before a retaining wall was constructed made from earth-filled bags. The main building structure and roof were made from larch, with lime-rendered straw bales filling the gaps and sheepswool for insulation. A damp-proof membrane offers protection, while a grass roof blends the structure into the hillside.

Photo: Malgosia Czarniecka Lonsdale

‘We’ve been talking about this for years, and lots of people have expressed an interest in helping us out with a natural building, so we designed this house specifically to accommodate and make use of all that extra help,’ says Simon.

‘We chose building techniques, such as the cob floors, that would be easy for large groups of unskilled people to learn.’ In the end, around 300 volunteers helped out with the project, turning the site into a big green-building classroom. ‘We attracted people from really diverse backgrounds, and our volunteers ranged from anarchist Italian students to retired naval captains. Regardless of culture or social status, that ideal of returning to the land is universal,’ says Simon.

Tellingly, his highlights from the project are less about the milestones that most self-builders tick off – windows in, roof on, first fix – than the experience of working with people. And having so much hands-on help during the build has set off a chain reaction; many of his volunteers have taken their expertise back to their home countries and embarked on their own new projects.

Photo: Malgosia Czarniecka Lonsdale

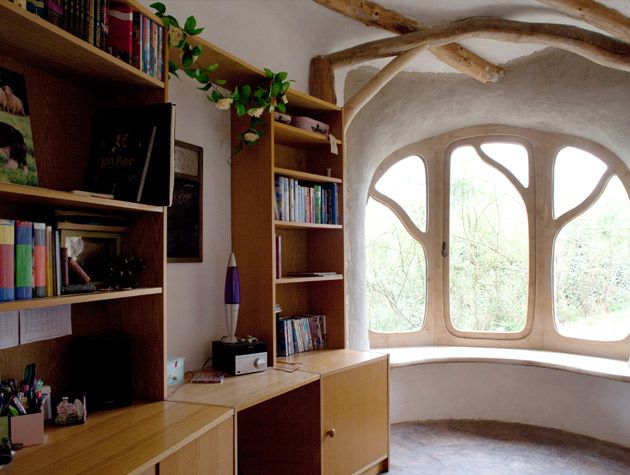

Although the eco-home is still incomplete, what has been finished is a tantalising glimpse of Simon and Jasmine’s vision for a highly finished low-impact home. With their branching tree-trunk window frames, the two children’s bedrooms have a fairy-tale feel; the rendered walls have an appealing sculpted quality, and the cob floors are polished to perfection with linseed oil and beeswax.

Eventually there will be a bathroom and master bedroom with the children’s rooms upstairs, plus an open-plan kitchen-dining-living space downstairs. Given how Simon gains such obvious pleasure from the process of building, and working with volunteers, might there be a tiny bit of him that never wants it to be finished?

‘I am wary of that,’ he laughs, ‘but no, it’s more about the practicalities. I either need a bit more time or more money.’ The project has cost £27,000 over two years.

Photo: Malgosia Czarniecka Lonsdale

Talking to Simon about the pleasure of using your hands to build your own home, and more specifically about his affiliation with timber, is infectious. ‘I love being surrounded by natural materials. I love the character I can see in stone. I love the wiggly bits of wood and what they evoke for me, and the fact that I can remember each one as a tree on the day I cut it down. You can’t compare that to a plank of wood from Siberia.’

Even if the aesthetics of Simon and Jasmine’s home aren’t to everyone’s taste, take note of their underlying approach because the issues they are addressing will soon become relevant to everyone. The self-builders of 30 years ago were often pioneering in their approach to energy-efficient building, far exceeding the Regulations of the time, but these days those methods are considered standard.

Now, the next big topic in building design is ‘embodied energy’ – how much energy it takes to manufacture and transport building materials, and the toxicity of those materials once installed in our homes. ‘I wouldn’t say that we’ve set out to prove something but we are trying to experiment and see if we can make a house that performs relatively well compared to a more technologically-driven modern building,’ says Simon.

Photo: Malgosia Czarniecka Lonsdale

He also thinks that his people-powered approach could have a wider application, whereby building methods and materials are specified because of their ability to be easily used and understood, therefore unlocking the potential for a more hands-on project. As Kevin says, ‘This isn’t just an example of how we could and should live. This is a clarion call.’