Controversial designer Thomas Heatherwick’s new book makes a passionate case for Humanising architecture

Thomas Heatherwick's controversial new book demands less boring buildings. And his argument for buildings designed with greater visual interest and more care for their users is powerful and convincing

Celebrated-but-controversial British designer Thomas Heatherwick has just published a new book, Humanise: A Maker’s Guider to Building Our World (Penguin, £15,99), which challenges the architecture profession over what he sees as its lazy habit of designing boring buildings. Heatherwick’s impassioned manifesto also calls out the construction industry for being complicit in what he calls a ‘blandemic’ of third-rate, Modernist-lite buildings, which has filled our urban landscapes in the past century. And he demands better buildings: ones that are more visually interesting; and designed with greater regard for the feelings they evoke in the people who encounter them.

View this post on Instagram

Boring buildings are bad for us

Heatherwick argues a desire for visual interest is actually a biological need hardwired into us as humans. He believes boring buildings are a real threat to our psychological wellbeing. We don’t have to go quite as far as Heatherwick does – when he blames some suicides on boring buildings – to agree that bland, uninspiring built environments are very bad for people’s wellbeing.

Modernism as cult

Modernism as cult

Heatherwick places the blame for all the boring buildings at the feet of the Modern movement, and an architecture profession still in its thrall. His description of Modernism as a kind of cult is convincing. There is something smug and perversely puritanical about the way those in the know (or, rather, in the cult) look down their noses at all forms of ornament and decoration – and at those whose ‘uneducated’ tastes refuse to show due deference to the utilitarian aesthetic of the clean line. Part of the emotional satisfaction of being in a cult is the sense of moral superiority that it brings; the sense of being apart from, and better than, the rest of humanity; often coupled with an ascetic self-denial. Isn’t that absolutely what’s going on when we define ourselves through our acetic-aesthetic preference for minimalism, and congratulate ourselves on our good taste, which the masses just don’t understand?

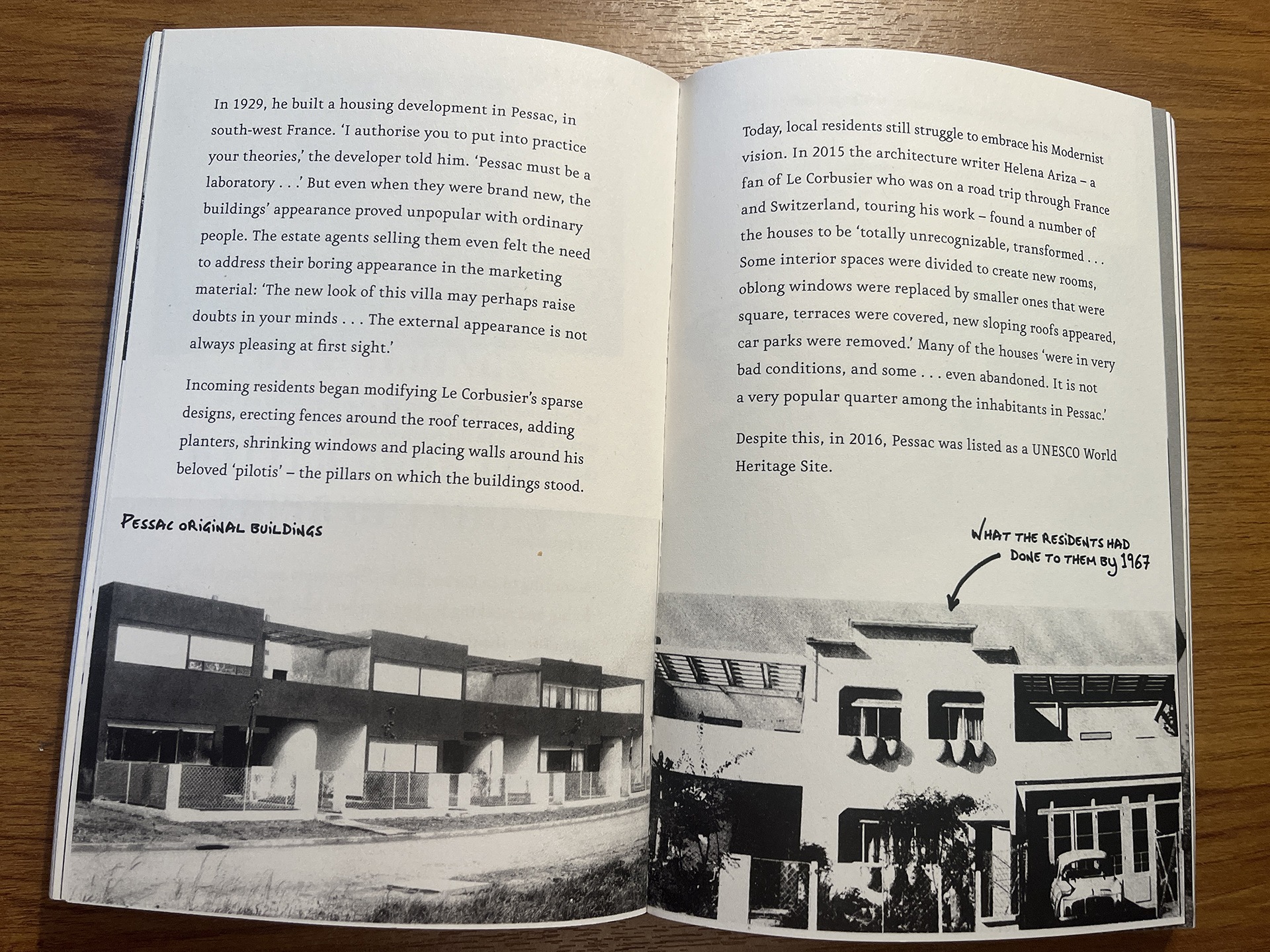

Few really want to live in a machine – even one designed for living. We have human needs that, for many people, Modernism’s austere creed just does not meet. We see evidence for this in the widespread failure of Modernist council estates (though, of course, there were many other complicating factors here, from poverty to poor maintenance); in current trends like cluttercore and the anti-minimalist backlash; and in the modifications made by the inhabitants of Le Corbusier’s Pessac housing development (see picture below). Perhaps clean lines work fine when they are crafted exquisitely from interesting and beautiful materials, less so when they are constructed from cheap, mass-produced elements?

Boring is cheaper

Boring is cheaper

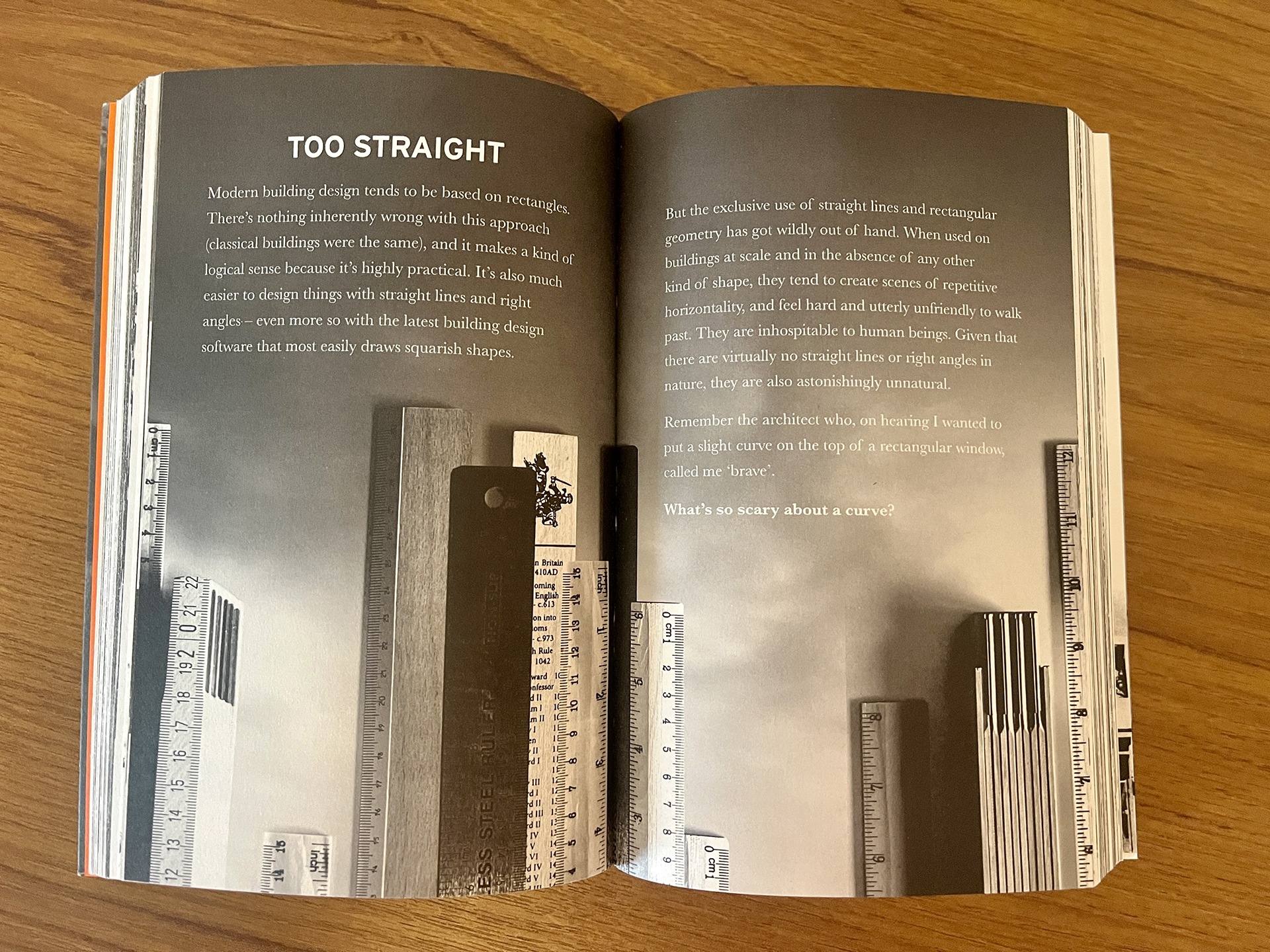

The designer is also absolutely on the money when he suggests that the straight lines and flat rectangular surfaces favoured by Modernism have given developers a brilliant excuse to construct cheaper buildings. In response to those who say we can’t afford better buildings, he cites the work of academic Michael Benedikt, who, Heatherwick explains, has calculated that Georgian and Victorian buildings were proportionally more expensive to produce in their day. He sees it as a question of priorities.

More visual interest

Heatherwick argues not for a return to the styles of the past necessarily, rather for buildings with a greater level of visual interest ie less flat, shiny, plain rectangles, and more detail. It’s a principle he tries to put into practice in many of the buildings he designs, such as 1000 Trees in Shanghai, the Zeitz art gallery in Cape Town, or Coal Drops Yard in Kings Cross, London. Regardless of what we think of his own buildings, there is truth in his decrying of the boring ugliness of much recent commercial new build.

Counter arguments

Architects and architecture critics have lined up to condemn Heatherwick’s stance – just look at the comments sections below any review of his book. Or see Rowan Moore’s solid take-down of some of Heatherwick’s arguments in his review for The Guardian. As Moore points out, Heatherwick pays little heed to the economic forces that have brought us so many dull buildings. He also rightly calls out Heatherwick for being too focused on surface ornamentation and not interested enough in how buildings function. Moore is correct, too when he points out that Heatherwick’s arguments are not new. (This is the post Post-modern era, after all.)

Traditional can be boring too

Heatherwick is wrong to pin all the blame on Modernism: most of the boring, samey, shoddy new-build homes put up around the UK each year are not Modernist in style, rather some kind of lowest-common-denominator traditional that owes little the hand of any architect. Modernism has no monopoly on bad buildings.

Buildings to last 1000 years

Many will argue that at a time in this country when a lack of homes is the real problem, a focus on looks is an indulgence. And it is hard not to have some sympathy with that argument. But Heatherwick is right to call time on hulking, rectilinear lumps of glass and steel destined to be torn down after only a few decades. He suggests we should design buildings that will last for 1000 years. Slightly hyperbolic, perhaps, but not a bad aspiration. And one that makes sense from an environmental perspective, too. With a solid structure, buildings can be remodelled to match changing needs.. Far better to build buildings that people love and want to keep, cherish and repurpose time and again, than to throw up unloved edifices and demolish them again after just a few decades. The question is: how to do that today?

Even if he isn’t completely clear about how the changes he seeks can be brought about, Heatherwick does cite some examples of buildings that meet his test of being visually interesting at distances of 40m, 20m and 2m, for example, Edgewood Mews housing estate next to the north circular in London.

Ongoing campaign

Ultimately Humanise is a provocative and interesting read with a kernel of truth at its heart. Perhaps it is a harbinger of a profound shift in tastes? Heatherwick sees it as the opening salvo in a decade-long campaign again mediocrity in the built environment. You can find out more about this campaign at Humanise.org.

Produced to coincide with the publication of Humanise, BBC Radio 4 programme Building Soul (all episodes now available on BBC Sounds) is a good introduction to the issues.

Whether you stand with Heatherwick or not, it’s always good to talk about what we want our buildings to look like.