Kevin McCloud on our desire for light and space and the battle to access the green belt

Our editor-at-large considers our desire for light and space and the battle to access the green belt.

Our editor-at-large considers our desire for light and space and the battle to access the green belt.

The idea of development remains an anathema to most Brits. We’re a nation of conservationists. We are also, in England, now the most populous country in Europe – with 395 people per square kilometre – and have always struggled to accommodate our population and our conservative, nature-loving instinct on the same island.

That instinct is expressed in a sentimental attachment to natural beauty, to the poems of Wordsworth, the landscape of the National Trust and the green belts of land that are enshrined in planning law, acting as the restraining rings around the girth of our towns.

And it is that instinct that led to the growth of ‘garden cities’ in the early 1900s and is now leading our government to build more garden villages, towns and cities. Exactly the same development as normal, we suspect, but with some more trees.

But what bit of countryside are we aiming to reproduce?

The naturalist Simon King gave a talk recently and said every time he looks at English countryside, he can only think of the sterility of the farm land, the paucity of species that live there and the way we employ fossil fuels and their products (diesel, plastics and chemicals) as the principle agents of control in what we mistakenly think of as a natural world. That description somewhat takes the shine off a pretty postcard of rolling fields and sheep.

As the ecologists Dirk Maxeiner and Michael Miersch put it: ‘Plants and animals are conquering the cities simply because the country is becoming an evermore inhospitable place for them. The vast agricultural landscapes of central Europe no longer provide them with space to live.

The main problem is over-fertilised soils, only suitable for plants that can cope with high concentrations of nitrogen. One example of this is the dandelion, which has become the dominant flower in many areas.

However, diversity – and this is the fundamental rule of ecology – only develops through scarcity. Farming is very different from how it used to be a hundred years ago. While biodiversity in settled areas is on the rise, it is diminishing in agricultural areas.’

And access for humans can be as scarce as it is for squirrels and lady’s smock. We feel we should enjoy the right to roam but, in truth, this is only possible in wildernesses – the national parks and mountains where someone’s livelihood is not dependent on a maximum acreage of crop being gathered in.

In truth, the battle for ownership and control of the green belts was won a long time ago by agricultural businesses. We can look at it out of our car window as we drive past, which is about as much as is worth doing because the view is no less sterile than the experience of walking through it. And in health terms, possibly a lot safer.

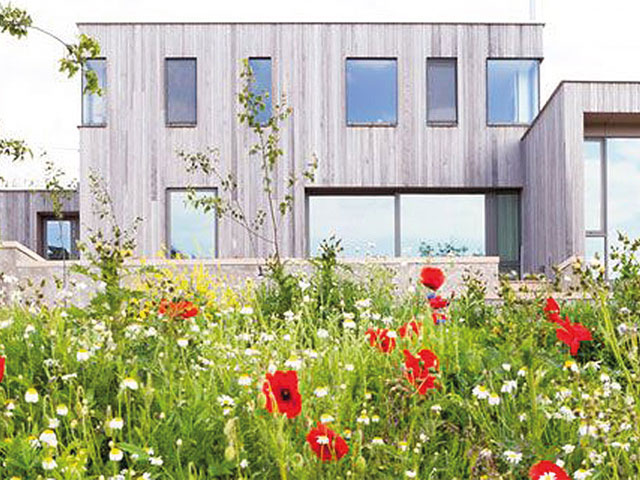

However, intimately and psychologically bound to that idea of the green belt is the idea of space. That somehow, as residents of highly dense urban environments or of mind-numbingly repetitive suburbs we have the right to access, thanks to the car, a world of green fields, woods and blue sky in which our chests can expand and our souls can sing.

Space has become a right, now. We each demand access to it as though it were as necessary as food or drink. Together with light, space has become the principle obsession of homeowners in the 21st century, part of the lexicon of modern builders, and for this we have to thank Le Corbusier who did, indeed, assert light and space as essential as food and drink.

Meanwhile in America, space has throughout the 20th century represented an objective to conquer, whether it was the race to outer space or the open terrestrial tracts of the vast country.

Unhampered by lack of land and the concomitant planning restrictions it brings, American developers could jump on the road bandwagon thanks to extraordinary large-scale infrastructure schemes put in by the likes of Robert Moses in New York in the 1920s and 1930s.

That saw the creation and expansion of suburbs set dozens of miles from the centre of Manhattan, made possible by car use. In Los Angeles, which in 1915 already had a sophisticated electric rail network and one car for every eight residents (the average being one car for every 43 people) the roadway was paved for massive suburbanisation through the sleepy villages and orange groves of the surrounding countryside.

As the eminent planner Peter Hall put it: ‘Los Angeles was a rehearsal, a laboratory, for the late 20th century urban future. Before 1914, developers would rarely dare to build houses more than four blocks away from a streetcar line, but by the 1920s, new housing was being built in the interstitial areas, inaccessible by rail. They now spread more than 30 miles from the centre of the city.’

Space was no longer unobtainable for the city dweller. It wasn’t just a psychological idea – it became a reality for every homeowner. And despite the problems that space has brought us in the 20th century – the total reliance on the car and a breakdown in sense of neighbourhood and community being just two – it remains one of the great talismanic romantic notions of architecture.

We still equate space and light with health, happiness and physical wellbeing. We demand spacious rooms with capacious windows to allow the healing light to variously flood, wash, pour, flush, inundate and scrub us clean.

Space and light were two qualities the Romantics sought in their early 19th-century landscapes, then mercifully free of chemical drenching. An emerging generation seems only interested in the light of a screen’s dim glow and the virtual space behind it.

Credit: Mark Bolton, Anthony Coleman, Matt Chisnall